For any query/comment related to this ebook, please contact us at haidar.ali@rekhta.org

For any query/comment related to this ebook, please contact us at haidar.ali@rekhta.org

About The Author

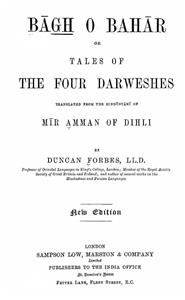

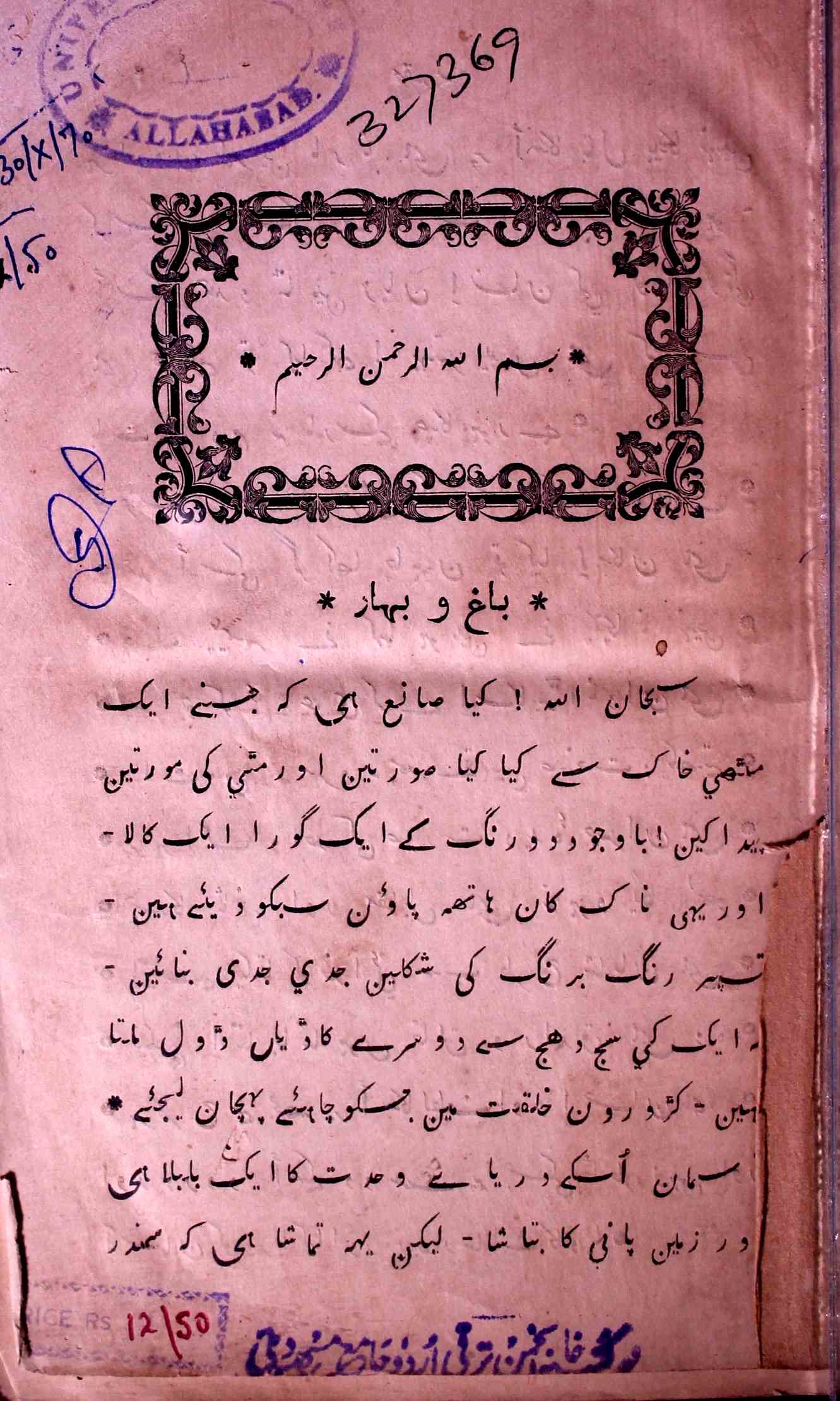

There is a living example of a living prose style in Urdu whose infinite appeal has stayed on and on over the last two centuries. In fact, with each passing decade, its popularity has increased and taken more readers into its magical fold. This book is Meer Amman’s Bagh-o-Bahar which, in fact, is a translation of Ata Hussain Tehseen’s Nau Tarz-e-Murassa. It is important to note that even while it is a translation; it reads like a fascinating narrative and stands entirely on its own. Its significance may be appreciated with reference to the fact that it has immensely influenced Urdu writers in the succeeding generations and given a direction to Urdu prose. It is a testimony of its great appeal to common human imagination that from Urdu, Bagh-O-Bahar has gone into French and English translations as well.

Meer Amman was born in Delhi around 1748. His family members had been the official functionaries of the Mughals ever since the days of emperor Humayun. He had inherited considerable property but Suraj Mal Jaat usurped them. Further, Ahmad Shah Durrani created havoc which added further to his misery. Meer Amman suffered badly and had to leave Delhi. He could reach Azeemabad (Patna) with great difficulty where he lived for a few years. As he did not have enough for his sustenance, he left for Calcutta to try his luck but there also he remained jobless for some time. Later, Nawab Dilawar Jung appointed him as a guardian to his younger brother, Mir Kazim Khan. He was not much enamored by this job and got impatient after two years. After this, he came into contact with Mir Bahadur Ali Hussaini who introduced him to John Gilchrist. This introduction to the great grammarian and linguist, John Gilchrist, got him an appointment at Fort William College where he worked as a writer and translator until June 04, 1806.

After joining the College of Fort William, he was first assigned the job of translating Qissa Chahar Darwesh. According to instructions from John Gilchrist, he translated it in pure Hindustani which was so well received that the College awarded him with a prize of rupees five hundred. It is important to note that even while he kept Tehseen’s primary text before him, he made many changes into it and developed his narrative which tells a tale of four derweshes with Azad Bakht as the central figure.

Meer Amman found a way with language beyond Arabic and Persian and developed his interesting tale in Hindavi, which often took leave from the established principles of grammar and came very close to the language spoken in Delhi. Critics have found fault with Amman for compromising with grammar and also disregarding the accepted norms of using singular and plural numbers, as well as masculine and feminine genders. In spite of this, Bagh-o-Bahar was too well received and emulated. Apart from Bagh-o-Bahar, Meer Amman also translated Mulla Hussain Waa’iz Kashifi’s Akhlaq-e-Mohsini as Ganj-e-Khoobi but it did not receive the kind of popularity that Bagh-O-Bahar had received.

The details of Meer Amman’s life are not available in the tazkiras. It is, therefore, difficult to ascertain the date of his birth and death, apart from other particulars. It would be interesting to note that Meer Amman, the formidable author and translator, was paid much less than his British counterparts.

A great champion of the Urdu language, Maulvi Abdul Haqq has been nicknamed Baba-e-Urdu, “The Grand Old Man of Urdu’’. All his life he waged a campaign to secure a rightful place for Urdu in the Indian sub-continent, and it was mainly due to his efforts that the All-India National Congress under clause 21 of its constitution adopted Hindustani (Hindi-Urdu) to be the national language of India. However, after the freedom of Indian sub-continent, Maulvi Abdul Haqq migrated to Pakistan and for the remaining years of his life worked for the promotion of Urdu in that country. Though he succeeded in getting Urdu declared as one of the two national languages of Pakistan, he met with tough resistance in his efforts to replace English by Urdu for official purposes.

Abdul Haqq was born in 1870. He was educated first in Punjab and then at the M.A.O. college, Aligarh, where he was influenced by Sir Sayyed, Shibli, and Hali. From Shibli he learned to pursue his ideal with zeal and fire, and from Sir Sayyed and Hali, the technique of objectivity and precision in prose, which later he developed into a style of his own. He went to Hyderabad in 1895 and, after serving as the headmaster of a local school and editor of a couple of Urdu journals, he became head of Dar-ut-Tarjuma, the institute of translation established by the decree of the Nizam for translating works on history, sciences, and philosophy into Urdu. He also worked as the first head of the Urdu department at the newly established Osmania University. In 1912 he was made the General Secretary of the Anjuman Taraqqi-e-Urdu. Undisputedly, he held that position until the partition in 1947. After his migration, he established the Anjuman’s counterpart in Pakistan, and also started the Urdu College in Karachi which to this day is the biggest non-government Urdu institution in India and Pakistan.

Maulvi Abdul Haqq, though married, left his wife, and never had a home of his own or personal property. He gave himself entirely to the service of the language he so passionately and consistently loved. His steadfast nature, his ability to work hard and long, and the remarkable length of his life resulted in the production of some fifty volumes of literature, besides his editing of the scholarly journal ‘Urdu’, for more than three decades. His style of prose is in direct line from the prose of Sir Sayyed and Hali. He possessed a unique skill of expressing himself in the simplest of language with a marvelous economy of usage and lively touch of colloquialism. His terse, concise, and succinct prose is close to the basic prose style of the Urdu language.

His works include little known manuscripts of fundamental importance for reconstructing the early history of Urdu language. His widely used works, though, are the ‘The Standard English-Urdu Dictionary’, and the ‘Urdu Sarf-o-Nahw’, or Urdu grammar. He died full of honor in 1961.

For any query/comment related to this ebook, please contact us at haidar.ali@rekhta.org

For any query/comment related to this ebook, please contact us at haidar.ali@rekhta.org

Write a Review

Jashn-e-Rekhta 10th Edition | 5-6-7 December Get Tickets Here