For any query/comment related to this ebook, please contact us at haidar.ali@rekhta.org

For any query/comment related to this ebook, please contact us at haidar.ali@rekhta.org

About The Author

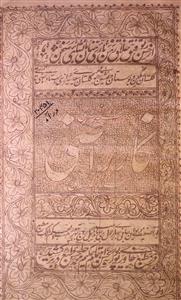

Born around 1810, Jani studied at the English school in Agra, a mere fifty miles east of Bharatpur. Jani was among the first generation of North Indians to receive a formal education in English. He later moved to Benares, where he studied at the Sanskrit College. By the time he completed his education, Jani, like many other educated young men of that time, was well-versed in Sanskrit, Persian, Arabic and English. But he developed a special affinity for Urdu, which had coalesced into a definitive shape only in the late eighteenth century. The details of Jani Behari Lall’s early career are hazy and conflicting. He may have started his career as a teacher in the 1830s at the school established by Babu Fateh Narain, a scion of the ruling house of Benares. In 1843, he was teaching at the Victoria College, Benares. When a newly appointed principal attempted to restructure the educational system in Benares and unify the Sanskrit and English sections, Jani was among the teachers who received these reforms. Eventually, Jani decided to explore other career options. In the mid-1840s, Jani Behari Lall joined the sixty-second regiment of the Bengal Native Infantry. He was the regimental schoolmaster. Jani travelled to many places in Bengal with his regiment going as far east as Dhaka. This was when the East India Company vigorously followed a policy of expansion through wars and conquered Punjab and a large part of Burma. The Doctrine of Lapse was also used to annex Indian royal states. Its army was always on standby, ready to march at short notice. Jani must have had the opportunity to observe these political machinations at close quarters for the eight years he was with the Native Infantry. This stint also allowed him to develop relationships with European officials in the military and administrative cadres. When his elder brother, Jani Bankey Lall, who was the vakeel of the state of Bharatpur at the Rajputana Agency, died in the early 1850s, Jani Behari Lall was requisitioned by the Bharatpur Maharaja to act in his stead as naib-vakeel. After the ruler, Balwant Singh, died in 1853, leaving behind an infant son, Bharatpur entered a period of uncertainty. Jani Behari Lall might have played a crucial role in ensuring a successful transition until Jaswant Singh (1851–1893) was placed on the gaddi. From 1854, Jani Behari Lall had a new role in the same setting. Instead of being a vakeel of an Indian state, he was now munshi or secretary at the Rajputana Agency. Working closely with the Agent, he might have managed diplomatic correspondence with its sixteen ward states. This role required a command over Persian and English, besides local languages. In May 1857, most regiments of the Bengal Native Infantry, including the sixty-second in which Jani had served, mutinied. It was a turbulent period for the East India Company as its officers tried to ensure that the mutiny did not spread to Rajputana. Though they could not thwart it, they were able to quell it through a combination of fortuitous circumstances at short notice. Unlike the ruling nobility in the environs of Delhi, none of the Rajput states, especially Bharatpur, supported the mutineers, which proved to be the decisive factor. The rebellion in the kingdom of Kutch, adjoining Rajputana, was also subjugated similarly. The East India Company, as part of its policy to exert better control in the aftermath of the rebellion, decided to depute Indians who had worked in its establishment to oversee the administration of its client states. And so it was that Jani Behari Lall was designated the dewan or chief minister of Kutch in 1858. Sandwiched between the two large provinces of Sindh and Gujarat and bounded by inhospitable salt-caked deserts, Kutch might seem a place where nothing significant transpired. But that was far from the reality. Kutch had its fair share of action: border skirmishes, assassinations, fratricides, and, once, in 1741, a Kutchi prince named Lakhpat, emulating the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb, usurped his father’s kingdom and imprisoned him until he died. Its long coastline facilitated a thriving maritime economy, and Kutchi ships called Indian Ocean ports from Zanzibar and Muscat in the west to Sumatra and Java in the east. Besides a brisk trade in salt and agricultural produce, Kutch was the entrepôt for African slaves and Malwa opium. Its importance in 18th-century trade networks of western India can be gauged by the fact that Tipu Sultan of Mysore had established a “factory” in Bhuj to further his international trading interests. After Tipu Sultan died in 1799, this investment provided the East India Company with an excuse to establish direct contact with the kingdom of Kutch as they sought to claim his assets. They soon deputed a Political Resident to Kutch, and within two decades, in 1819, manoeuvred to depose the reigning king. His five-year-old son was installed on the throne with the titular name of Maharao Deshalji II. When Jani arrived in Bhuj in 1858, Deshalji, now in his forties and unwell, still occupied the gaddi. As a dewan who had been imposed on the state, Jani Behari Lall might have faced a hostile reception from the numerous power centres in the Kutchi court. But Jani seems to have established his clout by deftly defusing a succession crisis precipitated by Deshalji, who wanted his younger son to succeed him rather than the crown prince. To exercise effective administrative control, Jani compiled and codified all the extant local laws. And perhaps, it was to print this Kutchi law code that Jani Behari Lall requisitioned a printing press. Having spent his youth in Agra, Jani Behari Lall would have been familiar with the printing press and its products. The Agra Akhbar, the first Urdu newspaper from the city, began its career in 1831. Agra’s first Persian weekly newspaper, Zubdatul Akhbar, came into existence in 1833 and was long-lived. The Agra Mission Press and the Secundra Orphanage Press, both established in the late thirties, printed prolifically in many languages. By the 1850s, Lucknow, Delhi and Allahabad cities had also emerged as significant print centres. One can imagine Jani as a diligent peruser of newspapers and a buyer of printed books in Urdu and Persian. One of his verses goes thus: “I am in love with books, say Raazi, because a book is a man’s best friend.” The printing press at Bhuj was known as the Kutch Durbar Press. It was the first to be established in the princely state of Rajputana or Saurashtra. No further details are forthcoming about the press Jani set up, but it became operational in 1859. The lithographic press could have been sourced from Bombay or Ahmedabad, and a trained printer might have accompanied it. It was from the Kutch Durbar Press that the aforementioned Urdu book was published in Hijri 1277 (October 1860). It was a book of poetry composed by Jani Behari Lall, who wrote Urdu verse under the pen name (takhallus) of ‘Raazi’. Titled Muntakhab Qasaid va Ghazaliyat [Selected Qasidas and Ghazals], the book runs 175 pages. Lithographed on cream-coloured locally made paper, the text is neatly laid in two columns with generous margins. The scribe who copied the lithographed text was Miyanji Abdulla bin Miyanji Ibrahim, a native of Mandvi, the largest port in Kutch. Abdulla wrote in a steady but slightly cramped style. The floral embellishments are, however, ineptly done. The book's print quality is mediocre, as might be expected in a newly set up lithographic press, perhaps operated by an inexperienced lithographer. The inking is uneven in most pages rendering the text illegible at places. The text does not contain a dibacha (foreword) or taqriz (laudatory blurbs), standard features of contemporary Urdu poetry books. The first third of the book comprises the qasidas or laudatory poems. The recipients of praise from Jani’s pen are mostly European military officials ranging from lowly lieutenants to colonels commanding his regiment. Jani would have worked with them during his stint in the Bengal Native Infantry. He also includes an application for redress, written as a long poem, addressed to the principal of Benares College in 1844. His ghazals, which account for more than half the book, were judged as competent by his contemporaries, even if he verged on prurience occasionally. The book's highlight is a biography of Jani Behari Lall, composed in Persian verse by a Kutchi poet, Munshi Amin Ahmed Sahba. Though it is composed in the highfalutin’ style characteristic of such encomiums, the qasida traces Jani’s career from his early days in Agra and Benares to his exploits in the Rajputana Agency at Ajmer and Mount Abu before he arrived in Kutch. He then mentions the high regard senior officials of the East India Company held him. At Kutch, he credits Jani with establishing the rule of law. Some of the biographical details in this article account are based on this qasida. As a prominent Urdu poet, Jani Behari Lall features in many tazkiras (biographical dictionaries of poets). Still, their authors, such as Lala Sri Ram, who wrote Khumkhana-e Javed, do not seem to have seen this book. Nor has Malik Ram, who profiled Jani in his account of Ghalib’s disciples, Talamiza-e Ghalib.

For any query/comment related to this ebook, please contact us at haidar.ali@rekhta.org

For any query/comment related to this ebook, please contact us at haidar.ali@rekhta.org