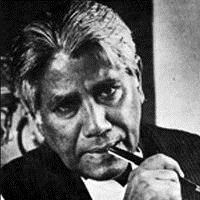

Profile of Akhtarul Iman

Pen Name : 'aKHtar'

Real Name : Akhtar-ul-Iman

Born : 12 Nov 1915 | Bijnor, Uttar pradesh

Died : 09 Mar 1996

LCCN :n92034947

Awards : Sahitya Akademi Award(1962)

Akhtarul Iman is a unique poet who set new standards for Urdu poetry, and whose poems are an invaluable part of the treasure of Urdu literature. He digressed from the popular genre of Urdu poetry, ghazal, and made Nazm the pivotal means of his poetic expression. He spoke in a language which, in the beginning, was rough and non-poetic for those who were interested in Urdu poetry, Taghazzul and Tarannum were not to be found in his writings, but over time, it was his expression which struck a chord with those who came after him. His poetry neither shocks the reader nor immediately captures him, but slowly, in an imperceptible way, awakens his magic and leaves a lasting impression. His thoughts are on illusions or melodic lyricism which cannot be confined to the realm, so he devised a paradigm that could cover as much of the sensory, emotional, moral, and social experience as possible. That’s why the expanse of poetic themes that we find in his writings are not to be found elsewhere. Each of his poems presents a new expression, tone, style and harmony. For Akhtar-ul-Iman, poetry was not a mental wave or a pastime. In the foreword to his collection of memories, he wrote, "My poetry, what is it? If I want to make it clear in one word, I will use the word religion. Any work that a person wants to do honestly, as long as there is devotion and sanctity that is only related to religion. Poetry was an act of worship for Akhtar al-Iman and he never recited his prayer-like poetry in Mushairas or poetic gatherings.

Akhtarul Iman was born on November 12, 1915 in a small town Qila Pathargarh in Bijnor district of western Uttar Pradesh to a poor family. His father's name was Hafiz Fateh Mohammad. He was an imam by profession and also taught children in the mosque. Food was their biggest concern. Due to his father's skirt-chasing nature, the relationship between the parents was strained and the mother often quarreled. His mother used to go away and Akhtar used to stay with his father for the sake of education. His father made him memorize the Qur'an but soon his aunt took him to Delhi and instead of keeping him with her, made him an orphan. Akhtar Iman studied up to eighth grade here. Abdul Wahid, a teacher of Moeed-ul-Islam, paid attention to Akhtar-ul-Iman's writing and made him realize that he has a lot of potential to become a writer and a poet. With his encouragement, Akhtar started writing poetry at the age of seventeen or eighteen. The school was only till 8th class. After passing 8th class from here, he joined Fatehpuri school where his fees were waived due to his condition and interest in education and he left his uncle's house and started living separately, and began to make a living by taking to menial jobs. In 1937 he matriculated from the same school.

After matriculation, Akhtar al-Iman enrolled in the Anglo-Arabic College (now Zakir Hussain College). Due to his fiery speech and double meaning poems, he was quite popular with the girls at college. He was heavily involved in non-teaching activities and was the joint secretary of the Muslim Students Federation. One of his speeches caused a strike in the college. At the same time, against his will, his mother married him to an illiterate girl, which ended in divorce. He used to take tuitions to meet his ends, where girls, too, came. Among them was a married girl, Qaiser, who was fascinated by Akhtar and in her old age. It was in her memory that Akhtar wrote his famous Nazm ‘Dasna Stations Ka Musafir’. This was not his last love. He kept falling for one woman after the other. Due to his low status and poverty, he I didn't have any self-confidence at all. He liked almost every girl he saw up close and then he himself became frustrated with her. However, these encounters were not merely infatuations. They were deep and intense, but on the other hand, his carelessness forced him to turn to some other woman. Then the feeling that these girls were unattainable devoured him. Then, he changed his mind. He realized that his ideal loved-one does not exist in this world. He named this inexistent entity ‘Zulfiya’, a girl which wasn’t a creature of this world, but a concept, a monster, and a condition, he saw a few of her glimpses in other women and began adoring them. Soon, he was considered a threat to the discipline of the college and expelled.

He went to Meerut where he was paid Rs. 40 per month. Akhtar did not like Meerut and he returned to Delhi four or five months later to become a clerk in the supply department. The appointment was made to Delhi Radio Station. The job fell victim to the internal politics of the radio station and he was sacked with the alleged hand of NM Rashid. After that, Akhtar somehow moved to Aligarh. He enrolled in a Urdu college, but could only complete his first year due to poverty and went to Pune in search of a livelihood and got a job as a storyteller and dialogue writer at Shalimar Studios. After spending almost two years there, he moved to Bombay and started filming. I started writing dialogues. In 1947, he married Sultana Mansoori. It was not a love marriage but was a successful one.

Arriving in Bombay, Akhtar-ul-Iman's financial condition improved, which was greatly influenced by his tireless work, and the lesson of which was given to him by the poet Mazdoor Ehsan Danish, who said, Bread comes from labor. Get in the habit of labor, my dear!”. Coming to the film industry in Bombay, Akhtar-ul-Iman got a chance to see the world and understand man in every way. He observed deceptions, lies and malice here. He said that he got real insight from the film world.

Akhtar al-Iman was himself the best commentator and critic of his poetry. He wrote the prefaces of his books himself and guided the reader on how to read them. He wrote, ‘there are those who are affected by changing socio-economic and moral values day and night. Where man is forced to make many compromises with life and society which he does not like. He makes compromises because it is not possible to live without it and He speaks out because he has a conscience." And this is not the voice of the conscience of Akhtar al-Iman alone, but the voice of the conscience of every sensible person of his time. His poetry is a reflection of the feelings of the same conscientious man in which there is no room for aggressive reaction in emotion. There is only the sound of emotion.

Akhtar al-Iman was a man of peace. During his 50 years of film career in Mumbai, Akhtar Iman wrote dialogues for more than 100 films, including Raftar, Mughal-e-Azam, Qanuun, Waqt, Hamraz, Dagh, Aadmi, Mujram, Meera Saaya, Dharmaputra, and many other successful films. He was awarded the Filmfare Award for Best Dialogue Writer for Waqt and Dharmaputra.

Ten collections of his poems have been published, including ‘Girdab Sab Rang’, Tareek Sayyara’, ‘Aab-Juu’, Yaden, Bint-ul-Lamhat, Naya Ahang, Sar-o-Saman, among others. He was awarded the Sahitya academy award for ‘Yaden’. The UP Urdu Academy and Mir Academy awarded him for Bint-ul-Lamhat, Maharashtra Urdu Academy awarded him for Naya Ahang, and Madhya Pradesh Government awarded him Iqbal Saman for his literary contributions. On the same book, he was awarded by Delhi Urdu Academy and Ghalib Institute. He died of a heart attack on March 9, 1996.

Tagged Under

Authority Control :The Library of Congress Control Number (LCCN) : n92034947